Ghost Stages of the Giro

In the calendar year the Giro d’Italia is the first of the three Grand Tours, but in age – and for many people – in status, it is second to the Tour de France. Italy’s three week adventure across a fractured country was first staged in 1909, 6 years after it’s French cousin and a comfortable 26 years before the Vuelta a Espana. Incidentally the Volta a Catalunya was first raced in 1911, but we won’t get into whether that counts as a Spanish stage race. Either way, it’s not and never has been a Grand Tour.

Grand Tours are defined by various factual criteria such as length in days, length of stages, World Tour points allocation, number of entrants and so on. But what really defines the Grand Tours are the stories, legends and feats of sporting prowess that have weaved together over the course of a century to form fabled and prestigious cycling institutions. From incredible endurance to terrible tragedy, from super human efforts to super charged effects; the Grand Tours have given us more than just bike races.

It’s in this regard that we believe the Giro d’Italia is far from second to the Tour de France. Whether it’s the suave silhouette of Coppi vanquishing all, Andy Hampsten battling the elements on the Gavia or Tom Dumoulin’s uncomfortable comfort break, the Giro conjures countless images of fame, glory, disaster and controversy. Every decade creates stories that become legend with improbable victories and unimaginable injuries marking stages in the memory forever. What we can’t remember are the stages that never were. Over the course of the Giro’s 100 editions there are been a handful of stages lost to unforeseen incident, races that never had the opportunity to become a sporting story but have a tale to tell. Ahead of the 101st edition of the Giro we take a look back at the Ghost Stages of the Giro.

The Hotel Des Anglais had been mysteriously vomiting syringes from its windows just before dinner

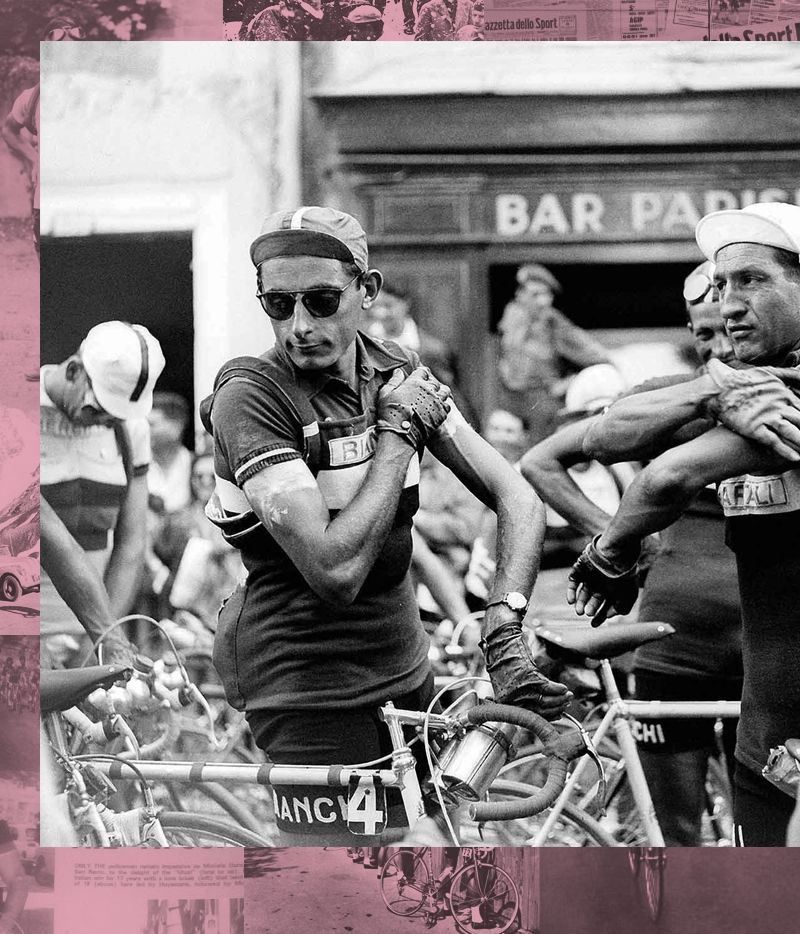

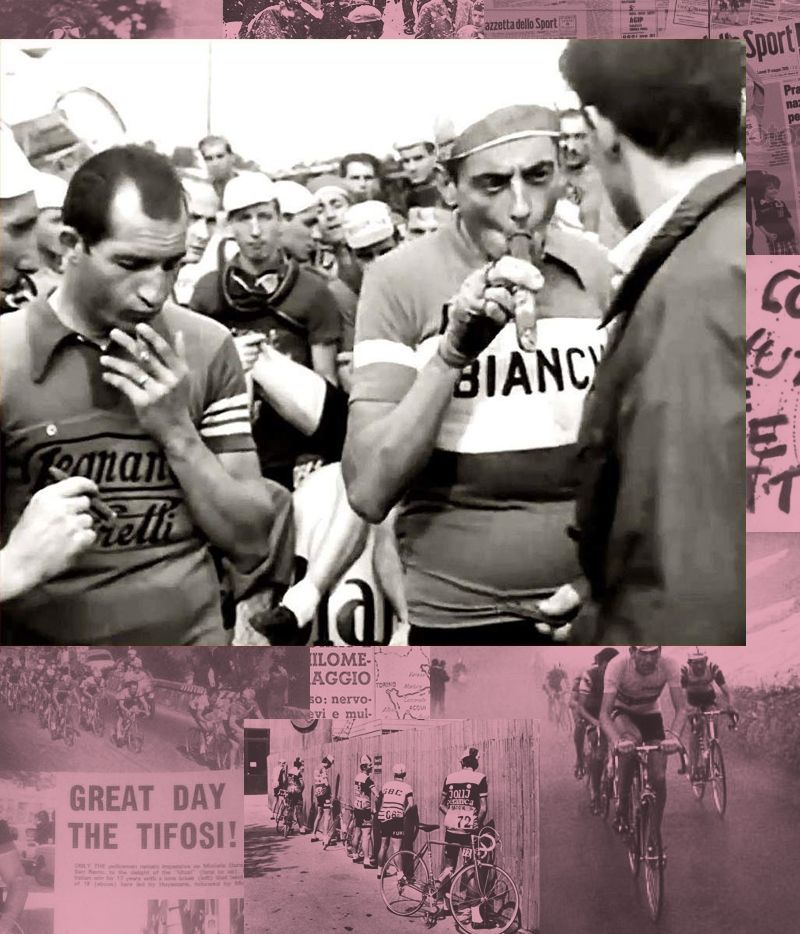

The first case of a stage disappearing from the results was in the first post-war Giro in 1946, a time when Coppi and Bartali graced the roads of Italy and a non-Italian was yet to win. This edition saw Bartali win his 3rd title, 47 seconds ahead of Coppi who had taken his first victory before the suspension of racing during World War II.

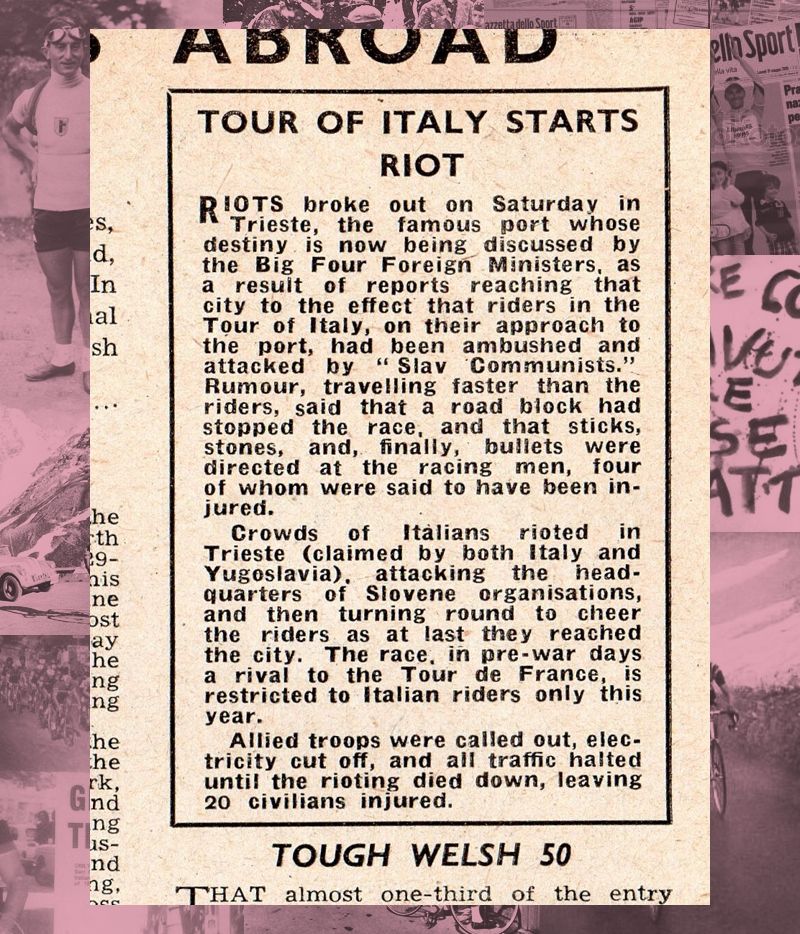

The Giro was dubbed the Tour of Rebirth, coming so soon after the end of the war and in the year of a referendum for Italy to become a republic. The country was divided almost 50/50 on that decision, something we can all relate to. Ravaged by war on terrible roads, through a country broken in many ways, the Giro was never going to be easy in 1946. Even the inclusion of Trieste was contentious, under allied forces’ protection and the subject of dispute over ownership with neighbouring Slovenia, the city served to remind that Italy was yet to even agree peace treaties following the war.

The stage set off from Rovigo and headed north towards Trieste where the peloton was met by Yugoslavs blocking the road. Things turned sour very quickly, when stones thrown by the protestors were met with a volley of bullets from the armed guards. The racers, having already taken cover, abandoned the stage. Only the Wilier Triestina team completed the stage, doing so with protection from a US Army vehicle. They were initially awarded the stage win, but the stage was later annulled with no winner and no time differences.

As the race moved further north it left behind scenes of utter carnage, riots raged in Trieste for several days, resolution to the problem would take several years when, in 1954, Trieste officially became part of Italy. The Giro had claimed it 8 years before, but history shows that no one was to win that day in July.

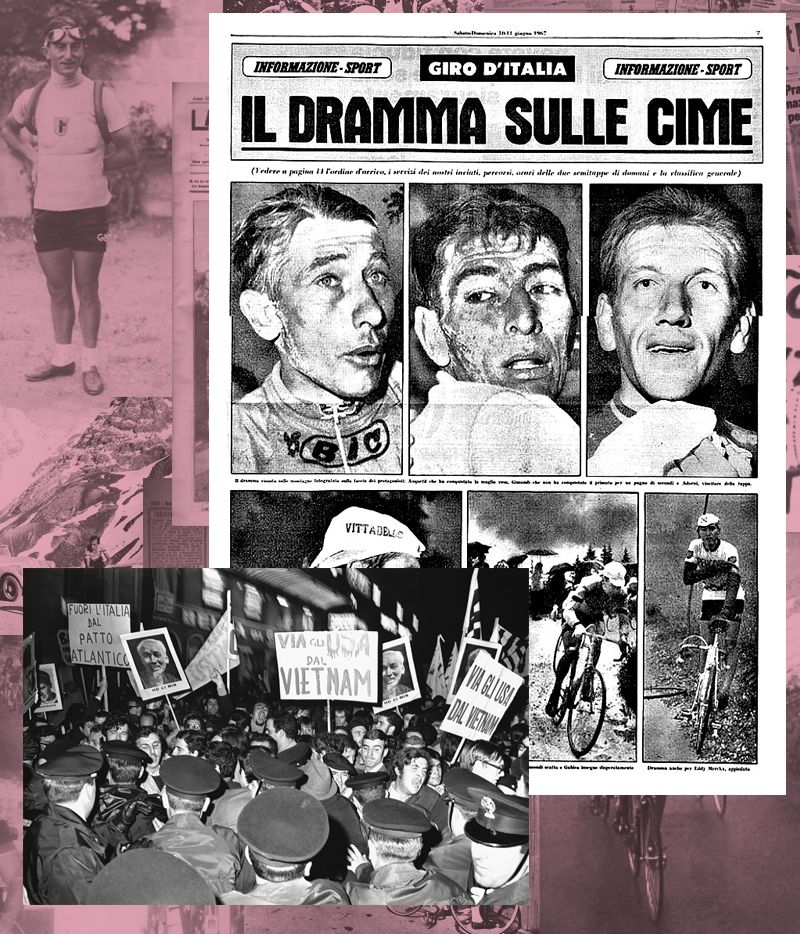

The Giro of 1967, won by Felice Gimondi, was supposed to start with a night-time crit around the streets of Milan. A ‘nocturne’ is something we’ve been treated to in recent years on the streets of London, a spectacle enjoyed by racers and fans alike in a carnival atmosphere. The atmosphere in Milan was quite the opposite in 1967 and the stage was cancelled before it even began with anti-Vietnam War protestors filling the streets that might have been lined with cycling fans.

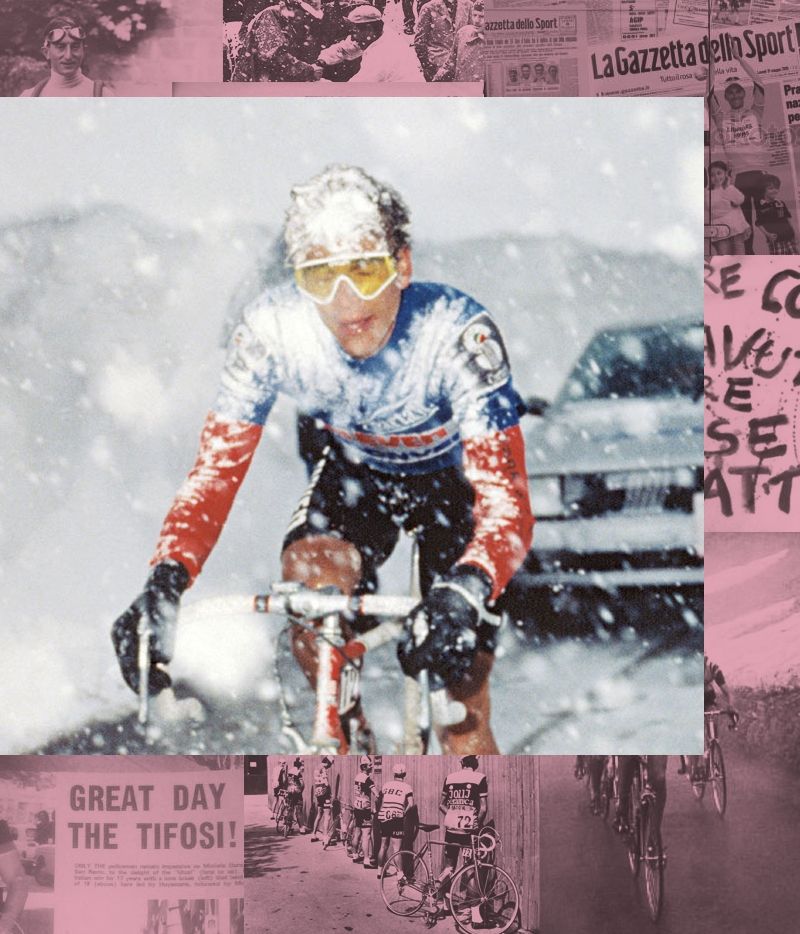

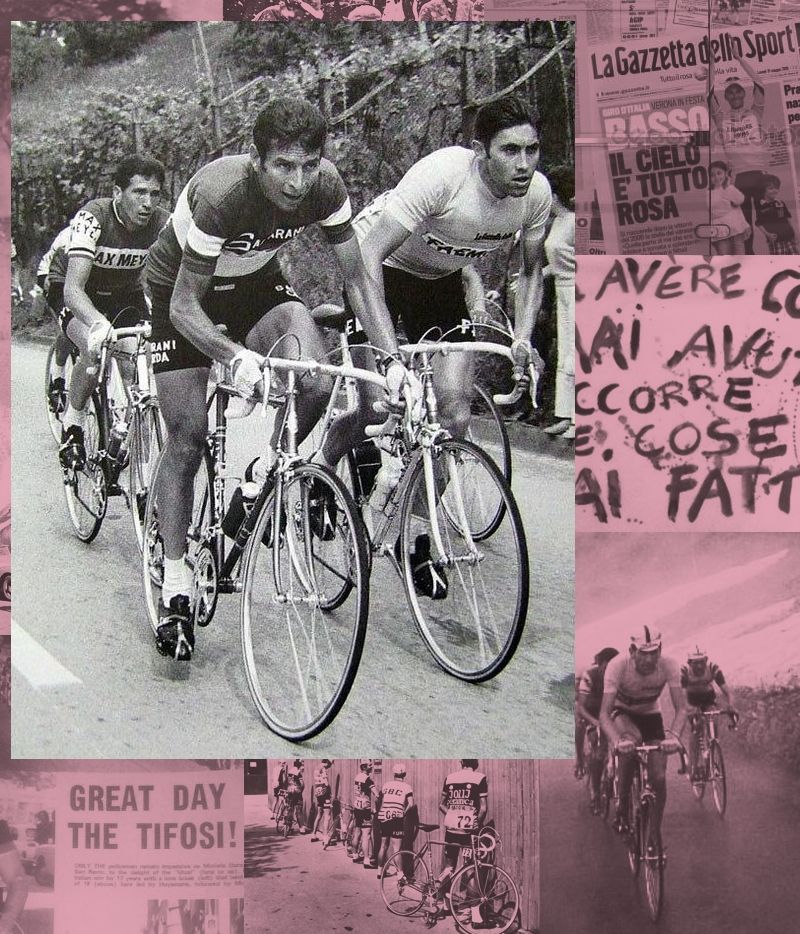

Whilst Stage 1 never happened, the 1967 edition boasted another ghost stage when Stage 19 was abandoned having begun in terrible weather conditions. The riders battled snow, fog and rain on the stage from Udine to Tre Cime di Lavaredo with Wladimiro Panizza of Savarani leading by 3 minutes on the vicious climb. He was soon overtaken by a peloton, beaten and battered by the weather and improbably fast — holding onto their team cars like skiers on a lift. Towed to the top of the mountain, Gimondi was first across the line, clearly benefiting from the most skilfully driven team car. The commissaires declared the result a farce and annulled the stage with La Gazette christening the stage The Mountain of Dishonour.

A simple case of bad weather saw the end to another stage in 1969 with the ascent of Marmolada cancelled due to heavy snowfall. The stage was expected to be the showcase and perhaps decider of the Giro, but the real excitement of the year had come after stage 16 when the leader — Eddy Merckx — was kicked out of the race for failing a drug test. The decision was shrouded in controversy with many claiming foul play and Gimondi even refusing to wear the pink jersey he inherited. Whilst the disqualification was never overturned, Merckx’s ban was – leaving him free to compete in the Tour later in the year. He has always declared his innocence and hinted at conspiracy, the Belgian parliament even demanded a retraction of the result and the smear to their national hero. Fruitlessly. A ghost doping result and ghost GC winner to go with the ghost stage? Who are we to say.

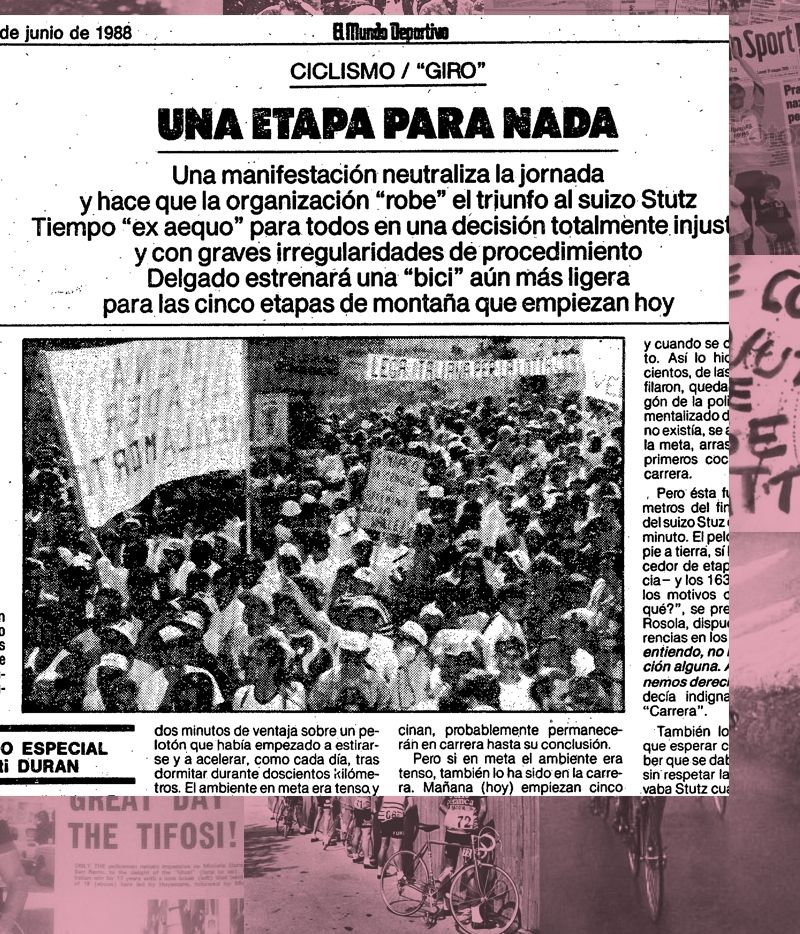

The flat stage from Parma was the last opportunity for the sprinters before the mountains approached. Werner Stutz solo’d from the bunch early on and rode without incident until about 3km to go, a truly wonderful way to win a stage for the Cyndarella-Isotonic team and only his second Grand Tour stage victory. Except that’s not quite what happened, despite crossing the line first Stutz’s victory was never ratified and the stage is recorded as ‘annulled’.

Unfortunately for Werner the trouble he encountered with 3km to go, whilst not a barrier to his victory was a huge problem for the chasing peloton. Around 50 environmental protestors blocked the road, upset by a local chemical factory polluting the Bormida River. Stutz expertly picked his way through the angry mob and on to a deserved victory, but the bunch were completely held up and couldn’t finish. Not only was Stutz robbed of the title of the day’s best rider, he wasn’t even acknowledged as the most skilful protest avoider.

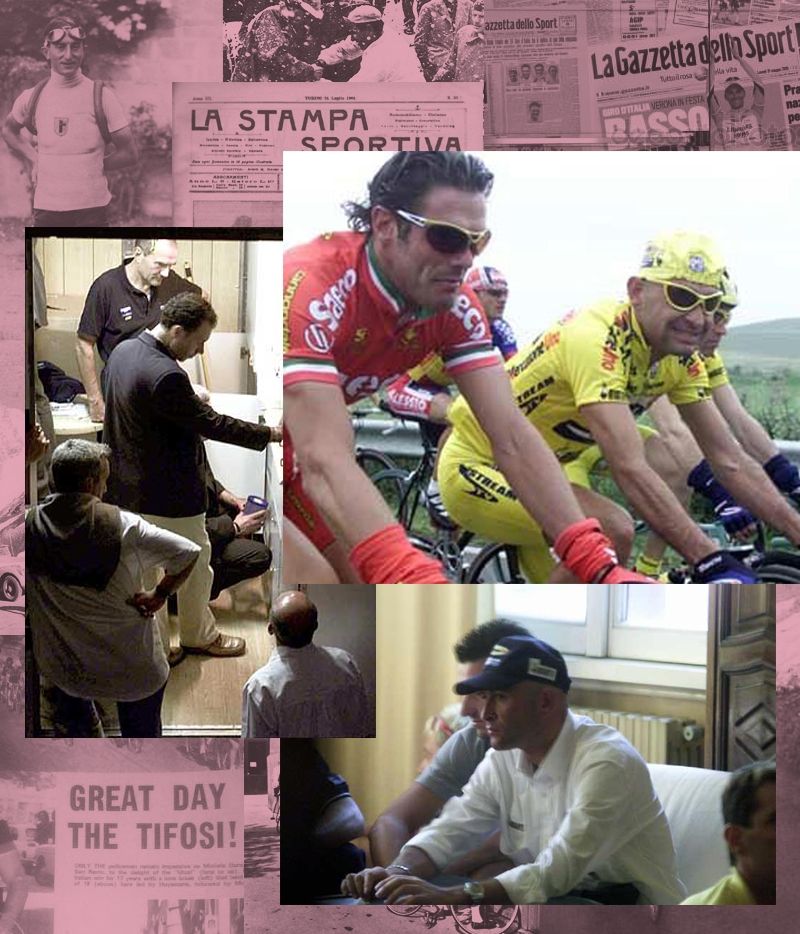

Whilst 1969 had the flavour of drugs about it, 2001 was a feast of doping scandal. Three years after the Festina affair that ravaged the Tour de France and cycling was in a sorry state — the 2nd Giro of the new century did little to perk it up. Perking things up was precisely the problem with 200 officers raiding San Remo team hotel rooms after stage 17. Pantani’s Mercatone Uno and Ullrich’s Deutsche Telekom teams were sharing the Hotel Des Anglais which had been mysteriously vomiting syringes from its windows shortly before the dinner time raid by police.

Among the substances still held in the belly of the hotel, police found syringes of insulin, containers of blood, cortisone, human albumin and ‘unlabelled liquids in bottles’. That’s some menu.

Police interviewed the riders until the early hours with the final searches concluding just a couple of hours before the wake up call for Stage 18. The poor innocent peloton were angry at what they deemed to be persecution from the authorities and demanded a shorter stage or cancellation of the whole race. A compromise was settled where only Stage 18 got the chop. Mario Cipollini remained furious, saying the stage cancellation was appropriate “after what we suffered during the night…” adding that “…things were done which upset everybody.” Since a lot of riders were clearly very sick and in need of copious amounts of medicine we can only sympathise with their rough night. Another stage becomes a ghost in the history of the Giro.

This edition of the Giro suffered particularly badly at the fickle hands of the weather with Stage 19 cancelled entirely and Stage 20 re-routed. Early on in the race ice had put an end to the climb of Sestriere whilst risk of avalanche did for the Galibier. With torrential rain prevalent throughout the tour, riders had climbed off with illness as early as stage 12 with both Bradley Wiggins and Ryder Hesjedal perhaps requiring some of 2001’s medicines. Wiggins never really recovered from a fall on Stage 7 and regrettable assessment of his own descending as “like a girl”. A ghost of the Tour de France champion only a year before.

Stage 19 had looked like one to watch with both the Gavia and Stelvio included, as well as Tre Cime di Lavaredo — the climb in which riders in 1967 hung on to cars to complete. Initially the two giant climbs were axed due to heavy snowfall and latterly the entirely stage, with organisers worried about the ice and temperatures of -20°C. Cavendish, holding the red points jersey at the time, was moved to tweet “I remember waking up excited to see snow. Then I became a cyclist.” a sentiment echoed by a large number of the peloton on the morning of our final ghost stage.

——

These Ghost Stages have been few and far between and, on the whole, fairly unsavoury. Hopefully with the Giro just around the corner we can hope for excitement and entertainment of a more sporting nature. Bad weather always makes for exciting racing, but lets hope The Beast from the East doesn’t make a return to completely ruin the race. Forza Giro, we don’t believe in ghosts anyway.